Where The Sea Flows Uphill

For reasons both geopolitical and sensory, no human had stepped within 300 meters of the Tijuana River Estuary in nearly a decade. For all but some migrating birds, hardy crabs, and fairy shrimp, the walls around the waterway were just too high, and the smell too acerbic to invite any visitors. The estuary—where the river flows into the ocean—is where everything lands as it flows downstream, and the region had been collecting runoff for generations while warmer temperatures encouraged algal blooms and fish kills. The pollutants were urban trash and raw sewage discharge from the Tijuana metropolis, and the cause for concentration in the estuary was inaction by government players due to disputed responsibility between the United States and Mexico, La Paz Agreement notwithstanding. San Diego County, north of the border, had turned the estuary region, formerly a patchwork of jurisdictions, into a singular park, joint-run between the state of California and Homeland Security. But, increased concerns of flooding and pollution gradually shifted the region from public space to the ecological equivalent of a demilitarized zone.

Various patterns persisted while human visitorship plummeted. Bird carcasses collected on the muddy inner shorelines as they succumbed to myriad toxins. The mouth of the river closed periodically—when large waves “plugged” the river with sand carried from offshore—which turned the estuary into a noxious lagoon. Scientists from the local universities on both sides of the border would wade in to collect samples of water, sand, plants, insects, and dead seagull; vagrants would lurk around at night to dump bulky trash; and Border Patrol would scan the Tijuana Estuary thrice hourly from a tower on the north side of The Wall. Illegal border crossings, which had reversed from south-to-north to north-to-south following the collapse of the California economy, mostly moved inland to avoid the pollution. Playas de Tijuana was no longer a recreational destination over the years as the smells and toxicity risk increased in the estuary, and the city of Tijuana re-zoned the region, save for the bullring, for industry as part of its 2030s infrastructure revitalization. Over the years, the buffer zone around the river widened, the tides sloshed in and out, the plants wiggled in the wind, and the people emptied out.

—

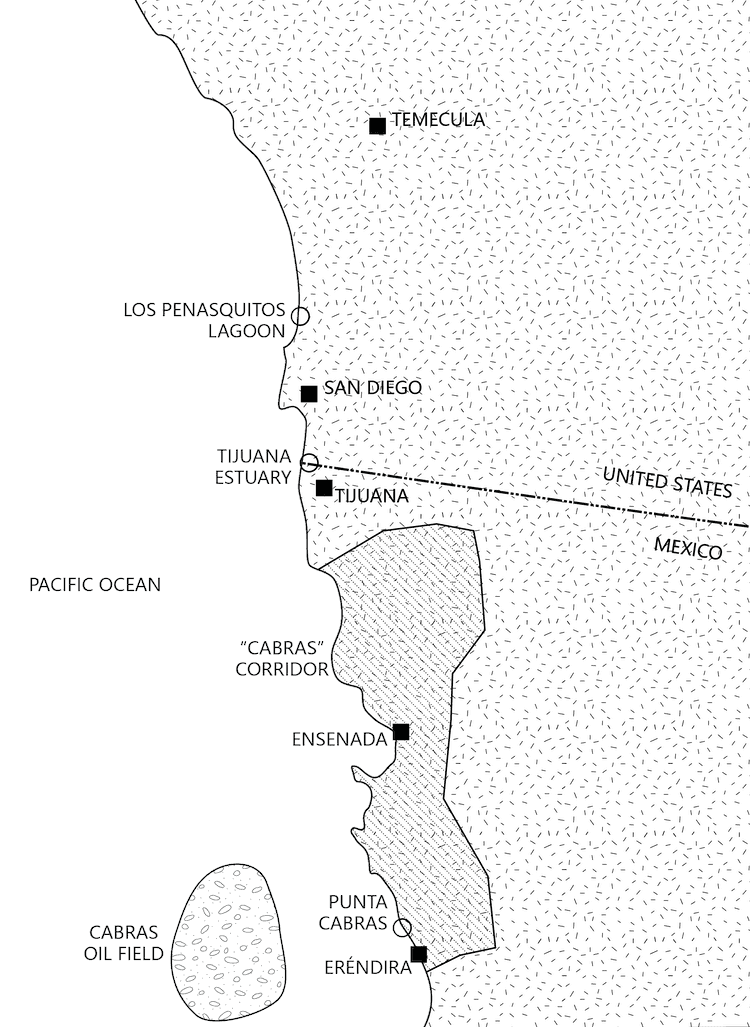

In the mid 2020s, a massive offshore oil field was found near Punta Cabras. As the Cantarell Field in the Gulf of Mexico dried up, Pemex redirected its oil infrastructure to the Baja Peninsula, fueling infrastructure overhaul to the Sonora and Baja states and a population boom in northern Baja. Water shortages initially throttled development, but a network of federally-funded desalination plants on both the Pacific and Gulf of California side eventually served the need, and Baja’s water infrastructure began to rival that of its northern neighbor, California. The plush pockets of oil employees fueled a cultural renaissance in Ensenada and an urban corridor, coined “Cabras,” ballooned with people, connecting the oil landings to the urban agglomeration.

The state of California underwent nearly the opposite: shrinkage and attempted infrastructural contraction. Sanctioned by the rest of the United States for an attempted separatism in 2026, prices for domestically-imported goods had skyrocketed and employing industries moved to other states. As northern Mexico grew and stabilized under a new government, economic conditions in Southern California faltered. Immigration patterns shifted. Immigration enforcement at the Border Wall became concerned with keeping the Californian tax base inside state lines and, whenever possible, keeping California prisons stocked with cheap labor to deconstruct roads that were no longer full of cars. I-5 remained heavily-used as transient oil engineers kept passport control at San Ysidro busy, but many smaller freeways shrank to trickles.

—

Rose knew this history, but in the dulled, distanced way that often comes when it is the environment one knows since birth. She was raised in Temecula, in the thick of the Southern Californian suburbia, and had seen it change. In the circles around San Diego, the housed population consisted mostly of military types and port workers with some remaining academics and medical employees. That is, on top of the new influx of American-residing Pemex employees. In the sprawl outside of the well-served downtown were crumbling remnants of residential regions, some developments disconnected from water mains due to budget and infrastructure failure, leading to the growth of a lower class that lived on pieces of part-time work and trips to public water wells. And, of course, a growing underclass who didn’t even have that, plus the surfers. The coast remained cool due to ocean cooling, but climate change-driven temperatures made inland zones more and more inhospitable. Temecula felt more like the Mojave with every passing year.

Rose’s parents both worked at the Port of San Diego and carried with them an air that, to Rose, seemed rooted in a nostalgia for good hard union labor and the life it could support. Rose felt them hypocrites for believing in the union but not coming home with greasy hands, but was still thankful for the stability at home. It was hard to find a job, and she knew she needed to get one soon, though her parents were gentle with her. She had seen many of her peers’ families move or fall apart as jobs crumbled and expenses rose, and didn’t want the same.

Her room rotated between being a mess and being immaculate, depending on her own mood and her mother’s demands. It was her space but at 19, a year out of high school and still living with her parents, the weight of their influence was felt. She badly wanted to leave: her social media recommendations were all about travel elsewhere in the world, and it was most of what she daydreamed about with her friends. She had never left California save some childhood trips to Nevada and Arizona in the winter, but those she barely remembered. She wanted agency, she wanted to move forward with her life, and she wanted to see the world.

Her dad gave her cash for helping with home repairs and she did some nanny work, but in the eyes of the state she was unemployed. Her evenings were spent drinking beers with her friends near the coast whenever she could borrow the car.

—

Rose’s friend Tucker lived nearby and he sometimes provided or joined the ride to the coast, adding color commentary to the trajectory through the hills. He had a part-time job at a restaurant but otherwise they were in similar situations: feeling stuck in a relative comfort of familiarity-at-home, not sure where to go next. He tried to make light of it by telling stories about the regulars and weirdos at the cafe. The drives to-and-from the coast sometimes had a 30° temperature difference, and their moods would swing, too, between moments of screaming bravado against frustration, and a dulled quietness of feeling immobile. The jaunts were quick bouts of fun, with music and friends and cheap food in little corners of the world that they felt belonged to them. It was mostly around the lagoons under the 5—Buena Vista, Agua Hedionda, Batiquitos, San Elijo, San Dieguito, Penasquitos, and more, depending on how far south they drove.

Their crew of friends attended the lagoons with enough regularity that they knew how to pick. Some of the lagoons would get plugged at the mouth, which would lead to stinking conditions for days or weeks on end for reasons similar to Tijuana. Some were kept open by old engineering structures and these they preferred, as the tides flushed the toxins out. They never went to the Tijuana Estuary: it was too far away, too smelly, and you couldn’t even get close enough to the water to see anything exciting. Sometimes they would go for a swim, but only in the ocean. The vastness of the Pacific was exhilarating in comparison to the intimacy of the lagoons. Every member of the group would release a yelp as they jumped into the dark waves, under the influence of low-calorie beer and moonlight.

When they sat by the lagoons, the friends would talk loudly and laugh. Sometimes it was just Rose and Tucker though, and their dynamic was quieter: they enjoyed long lulls in conversation, but it didn’t particularly bother them. They would listen for frogs, or the flap of birds wings, or whatever noises other creatures nearby made. It was hard to see the flowers at night, but on long summer days Rose enjoyed seeing the blooms at dusk, watching how some would close up and for others, the colors would shift as the sun set. Rose relished the quiet moments just as much as those with a hard laugh.

—

Elyssa knew that kids liked hanging out around the lagoons after dark. It was a minor scene that the San Diego County cities would occasionally rally against, but the homeowners associations were now too empty to take action: the rare noise complaint wouldn’t snowball into a county ordinance. Elyssa knew this because she had been one of those kids a long decade earlier, and now she was trying to follow youth culture patterns for her job. She was in charge of 18-22 year-old recruiting for the Civilian Climate Corps for the county, and was trying to tune into her inner 18-year-old: what would get her to sign up for this hum-drum sounding government program?

The CCC had been birthed under Biden’s administration nearly two decades prior, but the program had held as a relatively stable lifeline for unemployed Americans seeking work. The Californian branch of the CCC had suffered under federal restrictions, with local-benefit programs throttled as punishment for the Californian separatism movement. All that the U.S. Government funded in the state were those at the “National (B) or Global (A) Tier Benefit.” Namely, carbon sequestration.

What this meant in coastal Southern California was wetland restoration, and this was why Elyssa kept an eye on the lagoon kids. Wide-scale clean-up, removal of paved areas around the lagoons, and replanting of grasses and marsh plants was the goal, and the Californian homeowners who had, for over a century, fought so hard to pave over the entire southern coast finally did not have the money to resist a federal buy-out, even if for a pittance. There were many local benefits to this work despite the CCC’s classification, and Elyssa felt happy that she had a job where she genuinely thought the work was good for everyone.

As it turned out, Rose’s lagoons—symbols of youthful escape, stages for meeting and making friends, refuges to listen to nature—were also the top priority of the San Diego County Civilian Climate Corps.

—

Elyssa’s job was somewhat complicated by Pemex’s gravitational pull south of the border. To any young adult, if all you could expect was manual labor, why pull weeds and haul concrete when you could work an oil truck and make ten times the income? Getting a ticket across the border was tough to find, though, with success mostly found only by those with both American and Mexican passports. Successful in the legal sense, at least.

Esteban was glad he didn’t have to think about any of this. He had been a boy in Eréndira and hadn’t considered leaving: he loved the coast, felt close to family, and the jobs were plentiful. He had seen the region go from pescaderos to petroleros and witnessed Southern California contract into oblivion. Growing up, Esteban had read a story in Marinero Mexicano about how Baja’s terrestrial landscape was so barren and dry that it lacked soil and was thus starved of nutrients; in contrast, the ocean was abundant, so the ecosystem had various ways to push nutrients out of the ocean and on to land. The details were fuzzy in his mind, but the metaphor had stuck with him: the sea fueled growth on lend, and offshore oil had brought new money to the region as fishing had faded away. He enjoyed the boom, but knew the oil brought pollution and climate change.

He spent his weekdays bouncing between offices in Ensenada and refineries in Eréndira. His weekends were generally with his father, going on small fishing trips and watching movies. Sometimes in the mornings they would walk up the wash and into the hills, which remained an undeveloped corner of the city that people seemed to fear. Esteban’s father had told him that it was only dangerous when it rained, so most of the year they got to enjoy the wash all to themselves, and see the view of the boomtown with the Pacific in the background. Here, seeing his city thriving, Esteban felt cleansed of some of the sins of working in oil, which he took to heart but not enough to leave Pemex. His father loved the view on their hikes and appreciated all that his son gave.

—

Rose found one of the advertisements on a trip to Penasquitos. The group had parked and walked under the freeway to hide from errant eyes. The mouth was open and the air salty, but not briny. Rose lagged behind the group to use the bathroom, and the ad glowed in the dusky light on one of the walls of the building. “Love Lagoons?” Rose thought the question was silly, but she did love the lagoons, and looked closer. It was a job advertisement. Most jobs sounded tolerable at best, but Rose did actually like the lagoons. “Could this finally be my opportunity?” she thought, though she also acknowledged that she wondered this many times while applying to any other jobs she found online.

She opened the advertisement on her phone and pulled it up a few minutes later, once she caught up with Tucker and the group, tucked under the freeway. “Did you see this? We DO love lagoons.” She rolled her eyes and Tucker giggled.

“Sure, but you can’t get paid to chill by the lagoon. What’s the ad actually about?” said Tucker.

“It’s from the Civilian Climate Corps… I guess they are looking for people to help with wetlands stuff around here. Pay is OK.”

“Oh yeah, I only make that much when people are generous with tips. Are there multiple openings?” Tucker was reading the posting over Rose’s shoulder.

“Yes it looks like they have a few spots to fill! It’s all manual labor. Pulling weeds. Planting new stuff. Digging out trash. You can identify plants, right?”

“I can’t ID shit, but I wish I could. It’d be fun to learn.”

“Maybe we’d get to drive a government truck.”

“You’d be like your dad, driving a San Diego County Official Vehicle, hah!” Tucker took a long sip of beer, and the remaining sunlight shone off his eyes.

“If it means I have my own car, I’ll take it. I’m gonna apply!” said Rose. Tucker gestured to share the link with him as he took another drink. They smiled at each other and turned into the rest of the group, who hadn’t heard any of their conversation; it was loud under the freeway, and the waves were crashing not far away. Rose was tired of job applications, they all felt useless, but she knew another wouldn’t hurt. The group talked about movies they were watching, and who was moving to which other states. The next morning she submitted the application over breakfast, and Tucker finished his after the morning shift.

—

Weekends in Ensenada were riotous, and that was why Esteban generally avoided them. There was too much money sloshing around, too many young engineers looking for a stiff drink, and too many places willing to satisfy that desire. Esteban had a chip of resentment towards the engineers, many of whom were transient: either from the United States, or from Veracruz, or Alberta, or even Dubai. They didn’t have bad intentions but they didn’t like Cabras like he did, and he felt frustrated when they treated their time in Baja like a one-night stand. They were here because of the momentum or because of the money, not because of the place. He felt that the artists and the researchers who had followed the growth understood a little better, they were trying to pay attention to what was happening and trying to tend to the place, rather than seeking to skim off the fat and move to Cabo.

Esteban’s managerial skills had been growing, and he took a promotion to work in the Tijuana office, dealing more with Baja-wide pipeline planning rather than stuff at the refinery-scale. He took the train from Eréndira to Tijuana—nearly the entire length of the Cabras line—once a week and spent a night in corporate housing in TJ to avoid having to make the trip twice. He was happy that the only time he spent in Ensenada was from a moving train, and that he could still spend weekends with his father.

Tijuana had pulled back from its urban margin near the border, re-routing the border wall highway further south and giving the river more space. The strip had been naturally re-greened as wild scrub, with some paths walked-over by locals, but it was a mess, and the park was only sparsely maintained. Still, the office in downtown Tijuana was not far away. On the evenings when he would stay in the city, Esteban began to enjoy going for walks near the border, as the quiet gave him the same sense as going up the wash in Eréndira. The Tijuana River ran its course nearby and it smelled like sewage and tar, but it didn’t bother him too much: it was better than his days on the oil platforms. During one walk he saw a group of people, maybe twenty of them, in the zone between the Mexican and United States Fences. It was the first time he had ever seen a human between the fences in his years of trips to TJ. They were all bent over at the waist, plucking at plants, wearing protective equipment that made him feel exposed in comparison. Their vehicles sat on the American side near one of the regularly-spaced electrified gates, which hung open. American and Mexican border patrol loitered nearby. He kept walking, but moved a little slower to watch them poke at the sand.

—

Despite the advertising campaign being locally-focused, Rose’s application could have taken her nearly anywhere the CCC was doing coastal work. Some projects were particularly urban, focusing on post-flood home and infrastructure response in places like San Jose, metro Miami, or Cape Cod; others were para-urban, such as those replacing pavement with plants in the suburbs of San Diego or Houston. Rose was particularly intrigued by those that were decidedly rural, like nurturing oyster reefs in northern Maine, outreach to those cutoff from the mainland in the southern Louisiana concavity, or re-introducing diverse flora to northern Michigan. The more remote the work, the more her eyes glowed with the sense of something new, forward movement, an escape from the contraction at home. Rose watched videos and looked up facts about all of the places she could get placed, and began fantasizing. She knew many people who had moved to find work, but it always seemed hard: they often left before they found the job and scrounged to find support, whereas she could get a job and then move, with income secured.

Rose knew her local knowledge gave her a leg-up to do coastal work, or even stay local and work in the San Diego office. While waiting to hear about their applications, she and Tucker talked about Puget Sound, Galveston, and the Everglades, and while he spoke excitedly about these places, he would put down his eyes, and she could tell he was nervous to leave home. But they didn’t didn’t want to squander the opportunity for a good job. If she stayed local, her parents would be delighted. She hoped that wherever they went, they would get placed together.

—

On a gloomy June day many months later, Elyssa visited her Tijuana Estuary Team. It was a success story of her campaigns: she had managed to fill the roster with full-time recruits to work on the area which had been neglected for so long. The team was to pull up invasives that out-competed the preferable spartina and glassworts. They had seeds to plant, glasswort and cordgrass, genetically engineered to enhance their carbon uptake and sequestration capabilities. The team’s ostensible goal of changing the plant life was frequently deferred in order to pull trash out of the estuary, escort endangered birds to safer territories, and step to the side so that Mexican or American border control teams could complete their patrols.

The team of young people was out at work, and Elyssa viewed it as an opportunity to get glamor shots, of sorts, for the CCC’s social media platforms. It wasn’t pretty: the team wore filtration masks and heavy-duty gloves and waders to avoid the smell and toxins in the water. Still, she figured it looked exciting, in the way that anyone in a hazmat suit looks exciting, and sought to stage a photo with a smiling recruit. Elyssa was wearing protective gear herself, and waddled up to Rose, one of her “lagoon kid” successes, who was busy pulling up some young salt cedars.

“Happy to pose for a photo?” Her voice was muffled by the mask. “Hey Elyssa. Yea, sure.”

Rose had met Elyssa in her interview for the position, and had talked her through the benefits of staying local and working out of the San Diego office. Rose liked Elyssa’s character and her energy—it was a reminder that you could stay fun outside of the teenage years.

“Let me strike a pose!” said Rose, waving her pluckings in the air and sticking her tongue out. It fogged up her mask, but her smile shone through as Elyssa captured photos on her phone.

“How’s the team doing today?” Elyssa asked, tucking her phone away. Rose had become one of her go-to people, as she seemed to be on good terms with everyone in the cohort.

“We are tired! Plucking everything by hand is so much work…” Rose dropped her wads of plant material into the collective pile. “I liked the days of breaking concrete with the power tools.”

“Oh, really? That stuff is so noisy to me. I like the quiet of the planting days. But you know, I’m just a spectator…”

“And we’re your little minions!” They both laughed. “Maybe I’m just impatient. My mom used to do heavy machinery stuff at the port, and I think she loved how much material could move around so quickly. Now I get it too.”

“Got it. Aren’t the ports in Seattle even more automated than here?” Elyssa asked. As Southern California contracted, much of the Pacific port traffic had moved north.

“I think so, but none of us have ever seen it. Maybe someday.”

“Someday indeed. Alright Rose, thanks for the photo, I’ll see you later.” Elyssa walked back to her car and got the photo ready to share. It was nice to see Rose smiling despite the hard work.

—

Rose did not get her own government truck, but occasionally she got to drive one. On a crisp December day, she drove towards the group of people working the hills of the upper estuary, so that the team could shovel their pluckings into the pickup’s bed. She yanked the parking brake, hopped out, and gestured for the others to start filling the back. From the passenger side she pulled a water jug, and the field team took turns filling their water bottles after they shoveled their respective heaps of plant stuff into the back. This week’s work included removal of a few acres of invasives that had little benefit; the next week they would re-plant. It was December, and the rainy months were upon them: a perfect time to seed some new members of the ecosystem.

The team had become a unit over the seasons, establishing roles and reports and minor dramas. The restoration teams were two-year appointments and while there had been one drop-out and two off-schedule newbies, by-and-large, the roster was fixed. Everyone did the labor at the core of the job, but some had specialized beyond that: Rose had grown into a role including keeping things moving smoothly: some logistical, order-of-operations stuff, encouraging communication, and keeping the trucks topped-up on gas. She thought she was good at it, and it made her feel in-charge in a way she never had before.

Once loaded with plant debris, she drove the truck back to the CCC depot at the eastern end of the Zedler reserve, where the material was transferred to a larger truck which would take the green waste over to the Carlsbad desalination plant. Someone had figured out a good way to put the decomposing material to use up there and keep the plant running for less money, which alleviated some of the county’s water woes.

Rose stepped into the main office to return the truck keys. It was usually empty aside from some other CCC workers like her going about their days, but today there was a group of three in clean clothes standing near some of the large interpretive signs. She lingered, trying to hear what was going on, and was waved over by her manager, Robin.

“Everyone, this is Rose, she’s one of our field employees here with Zedler. Rose, these folks are from Cabras and they’re interested in collaborating on the border field!” said Robin. Rose felt flustered that she was being spotlighted as an employee but she dutifully stuck out her hand for a handshake. “Nice to meet you! What are you here to see?“

Esteban and his partner Ana shook Rose’s strong and dusty hand. Esteban was happy to see Americans hard at work in the Tijuana valley, a place he knew had been neglected for so long. He was there to try to establish an international partnership for the restoration work, hoping that some funding and labor from the Baja side could complement the infrastructure that the CCC had established to clean and revitalize the corridor as a green space. He explained this with energetic hand gestures.

Ana joined the conversation: “I’m an officer with B.C. Partnerships. and we think we can set up a structure such that Tijuana Parks can support and mirror what you all are doing on the northern side of the border.”

Conversation built, everyone was excited about recognition and teamwork. Rose and Robin drove the visitors over to the work site and showed them the operations. They learned how Esteban and Ana had already made inroads to the some Cabras companies who were looking for carbon offset programs and workshops for their employees: both were opportunities to work together. The border wall felt a little shorter.

—

In the evenings in the CCC barracks, Rose would listen to music and message her parents and friends. After meeting Esteban and Ana, she fired off a bunch of messages to Tucker. He had also gotten a corps job but in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and he was usually already asleep by the time she sent messages. Still, he always responded in the morning, and she just had to share the update. Tangible change through her work and partnerships like what she saw today excited her, a distinct change from the teenage malaise they bonded over before. She tucked her phone under her bed but her mind ran. Could she get a job with them when her CCC appointment ran out? Would the border become more permeable?

She flipped over in bed and thought of her parents. They had visited recently, on one of her days off: they had gone to see some music in Imperial Beach, and ate together. Her parents were proud of the work she was doing, and she was too, but whenever they said so she felt embarrassed that she had ever made fun of their jobs. It was nice to do the work. She wondered what they would think if she moved further away, or even just to the other side of the border walls.

—

Esteban and his father crested a ridge after huffing through a handful of switchbacks. It was going to be a blistering summer day, but they had left early and the heat was only with the sunshine. They were in their usual place, up in the hills upriver from Ejido Eréndira, catching up after a longer-than-usual span of distance. Esteban had been spending more time in Tijuana for his job, his work with the border, his time with Ana. It all felt valuable, but he felt separated from the simple joys of outings with his father.

His father was telling him about the good produce he had been eating recently, growing near Mexicali. Increased use of desalinated water for municipal use had given more flow back to the Colorado river and, despite long drought years, the bounty of fruit was still good. It was idle chatter, but there was always a philosophical edge to what his father would say.

“The best fruits are those grown close to home,” said Papi. Esteban almost laughed. “You just want me to spend more time close to you, is that it?” “No, no, that’s not it…” but Esteban knew better. His father continued: “I really do think the pitaya from this valley are the most delicious.”

Esteban signed and surveyed the river corridor below. He turned around to face the coast. Off in the distance, he could make out the oil platforms.

“I think I am going to leave Pemex.” He said, keeping his gaze offshore. He had been planning to share this news but he wasn’t sure how it would land; the job was one of the most stable in the area and had given their family a lot. But he wanted to focus more on what was important to him, and being a part of the oil industry had never felt right.

His father let out a small sigh. “That’s good, the fruit will be better without the oil.” said Papi.

Now Esteban did laugh. Of course his father was comfortable with it. Of course it would come down to some small quip about some small thing.

“Maybe you can spend more time down here when you quit. Or do you need to be at the border?”

“I do need to be at the border, but I think I can spend more time down here too, the trains are easy to ride.”

“How are things going with the park?”

“It’s going well! The Americans made enough progress to show how beneficial the work could be. We got the agreement passed for binational teams to work together out there on-the-ground. I think we could get more collaboration in the whole valley in due time.”

“You are amazing! Tell me, what are they planting there…?”

—

Rose had found an open door to Mexico. The partnership between the CCC’s San Diego Branch and Tijuana Municipal Parks had grown enough such that she was working closely with folks from Mexico both in picking up discarded trash and in city planning meetings about the estuary zone. The corps job had been a platform for her to grow: she had her own income, was making an impact, and connecting with others. At every junction, she saw the possibilities grow.

One evening, Tucker stayed up late and called Rose. She shared the exciting news about how the project was expanding, and Tucker sent his congratulations. He sounded tired, though.

“Our project doesn’t have anything like that going on!”

“Your project is cool too, don’t worry.” Rose knew he didn’t feel completely at home out there. He was always complaining about the sand bars on the east coast.

“I guess so. I am starting to have some more friends out here; I can take weekend trips to the big east coast cities. Have you been able to visit Tijuana, by the way?”

“I haven’t in a while, but I think I’ll visit soon. Actually, I think I can get a job there.” Rose explained. “Tijuana Parks said they need people on their restoration engineering team, and that they might be able to sponsor a visa.”

“Dang Rose, that’d be powerful. Maybe you can get me a job, then! I don’t think anyone stays in the Outer Banks, but I could go up to Norfolk or D.C. to keep working on the coast.”

“I know you miss the dry summers here, though.”

Rose held it close to her heart that they had stayed connected over the years. At the end of a long week in the field, someone on her team would bring beers over and this made her nostalgic for the lagoon days. Tucker was gone, and that friend group had fallen apart, many folks being pulled away by jobs or water availability or family needs. Some of the lagoons looked the same; some had been modified by CCC or other restoration efforts. But she hadn’t seen some of them since before she started working, and she certainly hadn’t seen Tucker.

—

The partnership between San Diego County CCC and Tijuana Municipal Parks was not necessarily unique for the Corps—there was another very active international management pact in northern Alaska and Yukon, and a few cases on the desert-to-marsh gradient along the Texan border—but the teams found they couldn’t look elsewhere for a rulebook. The Tijuana Estuary was the Tijuana Estuary, that was it, and the particularities and history of the place had to be reckoned with to make it healthy and to meet their goals.

The watershed of the Zedler reserve had been cleaned up enormously by work on both sides. They settled on a model with Mexico paying for the heavy machinery and the American CCC providing the labor. Together, teams of workers picked up enormous amounts of trash, removed acres of pavement where once were roads, abandoned homes, and airport runway, encouraged the growth of ecologies that could trap pollutants, and experimented with various techniques for the removal of surfactants and PFAS/PFOA chemicals from the water and soil. The Mexican side spearheaded change in urban waste, setting new norms around landfill pickup, litter, sewage, and chemical discharge. San Ysidro and Imperial Beach, both just north of the border, began to follow Tijuana’s model, and also refined their strategy for buyouts to give the river more space to flood without risk to life.

—

Despite that they cut a watershed in two, despite that thousands of lives straddled them, and despite that their role in keeping people out of the Tijuana River ecological zone was increasingly unimportant, the border walls remained. Rose could effectively travel across them with her new job at Tijuana Municipal Parks, which put her in the same class as Pemex engineers and managers, zooming through the pre-approved lane at border control. She felt she didn’t deserve it, but she relished the luxury. She had her own apartment in Tijuana now, and would, on the weekends, drive up into the baking inland heat of Temecula to see her parents and friends. She had been able to widen her door through the border to others, getting some of her CCC colleagues hired to permanent jobs in Mexico, and helping maintain volunteer programs with some travel going both ways.

Elyssa would sometimes be asked to visit other CCC sites or other municipalities to share her success of recruiting and action. Rose got to go on some of those trips, and her world opened. She saw the southern Louisiana concavity by plane and by boat, meeting with leadership that was decentralized throughout the region in a way she could hardly imagine. She was able to bring her mother as a guest on a visit to Puget Sound, where they saw how the ports were restructuring around greener shorelines. (Her dad, too old to travel easily, relished the stories back in Temecula.) She visited New York, where the largest urban coastal protection project in the Americas was in its second decade of construction, and where Tucker now lived. He was engaged to be married and now happily surfed the jetties out on Long Island, but he said he still hated the humidity.

Elyssa and Rose had grown from a mentor-mentee relationship into colleagues and friends, and they loved travelling together. Through her successes, Elyssa had moved up in the Civilian Climate Corps and now worked at the California state, dealing with plenty of CCC work off the coast: ag lands in the Central Valley, Sierras fire management, urban cooling in the Inland Empire. Still, she came down to San Diego frequently and would meet with Rose. She found it ironic that Rose had been pulled south of the border despite efforts to keep her with the CCC, but admired how Rose kept one foot rooted in California. Despite the distance and their age difference, they both enjoyed laughing about being lagoon kids.

—

Esteban and Ana had much to learn from Elyssa about recruiting, which they now needed to lead an environmental nonprofit in Tijuana. The CCC’s federal funding gave more flexibility than they could mirror, but Pemex had deep pockets and reparations to pay. The corporate offsets game became one they were willing to play. The population boom of the Cabras corridor brought in plenty of young people with time and energy, and the Zedler reserve’s success story fueled excited action nearby, as the LA River had modeled further north in the decades prior. Esteban led on-the-ground work—he knew the plants and the fish, and he found he could share his excitement easily with their volunteers—while Ana worked on the finance side. For both of them, the greatest joy was getting some of the transient population to see what was going on beneath their feet, to stay long enough to know where the water came from, and where it was going downstream.

The two of them had settled in Tijuana, which was more urban than Esteban ever thought he could love. But as the river park grew and the trains outside the city ran more regularly, he could find himself in a quiet river valley with relative ease. Ana was a city person, and so they often spent weekends apart: Esteban under the sun, Ana at home with a book. Their love grew through their projects together, however, and trips down to Eréndira were now as a pair. On one trip, they managed to recruit some young engineers sitting across from them on the train to volunteer on the weekends. Ana felt sure that once they saw how hard it was to clean up oil, any reasonable petrolero would quit their job. For Ana, Esteban was an exemplar ex-Pemex worker, and they hoped more would follow suit.

They often took walks along the river at night, routes similar to the one during which Esteban first saw the CCC workers, and he loved reflecting on that chance encounter that changed the trajectory of his life. The sewage stench was gone, and only a little tar remained. He was proud of the tangible change everyone had made to the region. Fishing near the river mouth was still discouraged due to remnant pollutants, but plenty of people—desperate for food or for recreation—still did. He knew there was work yet to be done.

—

Esteban’s father made a trip up to Tijuana and, in between seeing the couple’s apartment and some urban attractions, the father-son pair essentially recreated their Eréndira routines. They went for a short hike, they watched a movie on a small screen at home one evening, and they rented a small boat to go offshore. It was like the boat at home, a 20 wooden hull with blue trim. It felt comfortable to them both, and they left shore early in the morning to enjoy the calm seas.

Once out on the water, Esteban noticed his dad getting ready to clean their catch. “You shouldn’t eat the fish here, we should just enjoy catch and release.” “Why not eat the fish? Is the water is bad?” “The oil platforms release some chemicals and the fish collect them—it’s just not good for you. We would have to go further offshore.” “Ah.” His father started putting away his knives. “The fish will be better without the oil.”

Esteban chuckled. He pulled his hat deeper over his eyes and tossed his line out. It was an exceptionally clear day. Far to the south, he could see dots on the horizon: the oil platforms. But closer to them, on shore, he saw grassy green hills and the city he now called home.

—

For reasons both geopolitical and sensory, the Tijuana River Estuary was a vibrant and beloved part of the Southern California coast. After nearly 15 years of work by teams of laborers, planners, politicians, and anyone who would lend a hand, the region’s ecosystem was rebounding, and the parks were popular for locals both Mexican and American. When the mouth of the river became plugged, there was no longer the need to open it for pollution dispersion, and seals would sit sunning on the sand berm until the river flowed again. People walked near the border walls, on either side, and there was an open contract between San Diego County and Tijuana Municipal Parks to manage and monitor the region jointly, sharing policies and ecological goals.

Restoration engineers began to use the estuary as a success story in Southern California, a case where enough had gone right that some birds and fish began to return. People did, too. Although demolition had been one of the dominant goals of the project, some facilities had now been re-established up on both American and Mexican sides of the preserve, as a way to invite San Diego and Tijuana city-dwellers to spend a day in the scrubby river valley and marshy river mouth. The Cabras train line added a new, northwestern-most stop, right near the bullring, which got Pemex commuters closer than ever to the ocean.

The border guard no longer felt that their main workload was surviving the stench: it was now fishers who would try to fish through the border walls to get to the good ponds. Some surfers realized discarded material offshore had improved the waves, and the water quality was good enough that they wouldn’t risk an ear infection. They both had to be shooed away, but often lazily: as the flurry of the CCC project ended, the region returned to a slower pace of change. The tide continued to sweep in and out of the Tijuana Estuary, as it had for millennia, and the Santa Ana winds shook the grasses, cooling off the heat of the day.

All photos are the author’s, except for the last, found through Wikimedia.